(some possibilities of) Rural Belongings | Jade Montserrat and Daniella Rose King

1. Introduction

Daniella Rose King

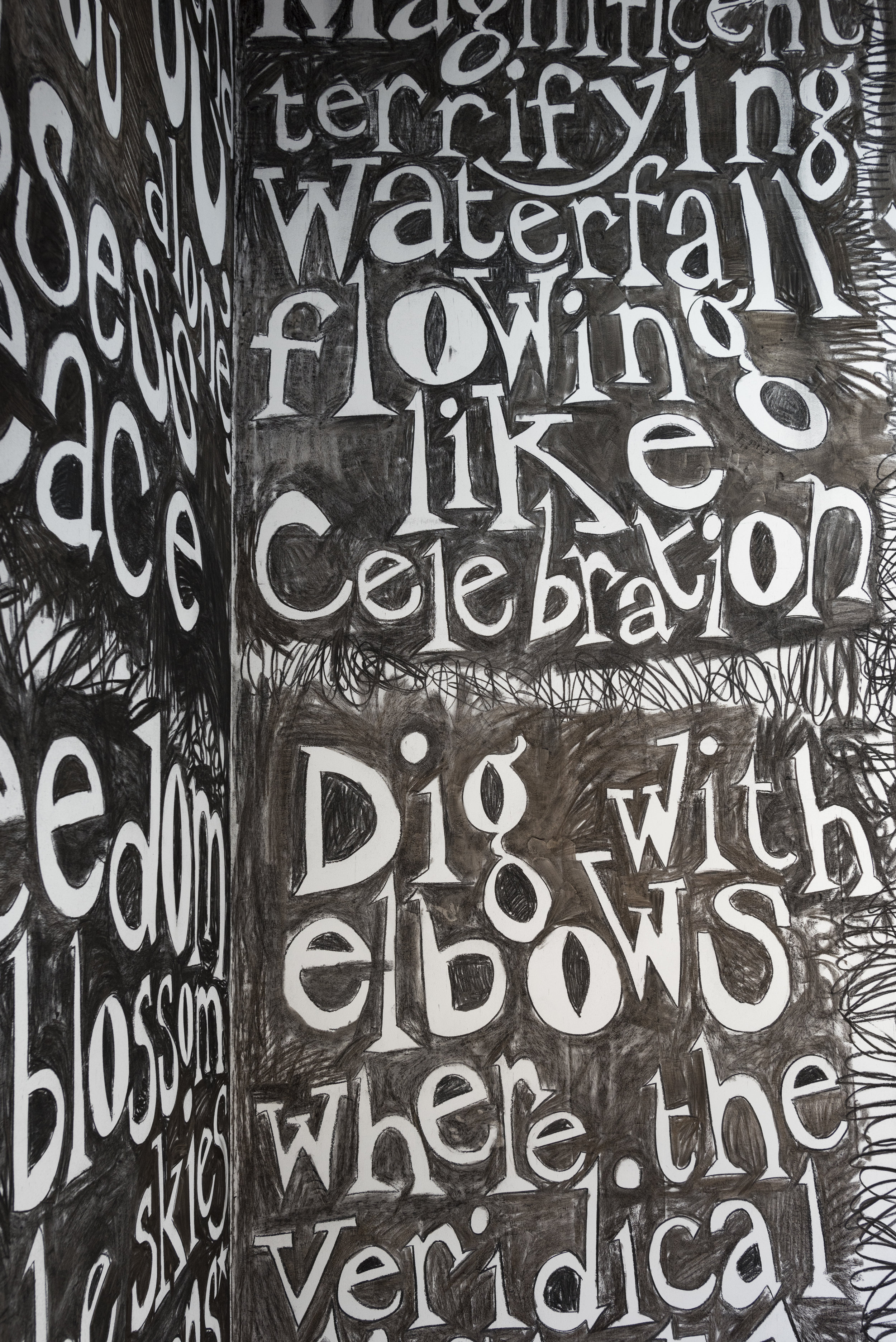

The text that follows culminates months of sporadic yet sustained conversation, exchange, reading, writing and thinking, between Jade Montserrat and me. The focus of our conversation is meandering, and traverses ideas of geography, place(making) and belonging, particularly as it pertains to our own experience as women of the black diaspora. Montserrat’s Untitled (The Wretched of the Earth, After Frantz Fanon), 2018, a charcoal wall drawing I commissioned for the exhibition “The Last Place They Thought Of” held at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, (April 27–Aug 12, 2018) acts as an anchor for the discussion. The exhibition featured work by four artists: Lorraine O’Grady, Torkwase Dyson, Keisha Scarville, and Montserrat, and sought to explore how histories of racial, sexual, and economic exploitation and their attendant exclusions and violences, have informed our understanding of, as well as the realities of our environment, geographic and thus spatial paradigms and their reproduction of uneven social relations. For this exhibition, Montserrat spent three days installing an ephemeral and site-specific work in the ICA’s ramp space, creating an installation that finds inspiration in practices of protest, public murals, performance, literary traditions and testimony, and drawing. She borrowed snippets of text from a plethora of authors, including: bell hooks, Toni Morrison, Dionne Brand, anonymous Philadelphia graffiti artists, Josephine Baker, Frantz Fanon, Donna J. Haraway, Adrienne Rich, Aristophanes, and Katherine McKittrick. Montserrat plays with abstraction and amplification to map a literary geography of the black Atlantic that speaks to how legacies of racism and sexism converge with the land. We nicknamed the piece “contagion” (it was too late to change the title in our printed materials) as a nod to the line “A contagion of boldness; I made you with love” and for the contaminating effect of the charcoal in the space. Many a visitor got too close and found their clothing smudged with ash. Montserrat was particularly excited at the thought of this organic material—carbon, which is the building block of all organic matter in the universe—departing the gallery space and moving into the world. It is a covert (or very conspicuous) traveler, hitching a ride on clothes, tops of heads, bottoms of shoes, and even stowing away in nostrils…

2. Our Beginnings

Jade Montserrat and Daniella Rose King

Our conversation about blackness and geography, in regards to the UK, began from a place of personal history, it could be said. We both identify as black British—via the Caribbean, and were born in the same hospital in London, so we recently learned, only a few years apart in the 1980s. But that’s where the similarities end. Montserrat was raised on a 200-acre estate in the North York’s moors, and King was raised on a housing estate in north London. It is clear to us both that these distinct geographies have shaped us, and with that our individual senses of belonging, alienation, and space. Paul Gilroy in his seminal book The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness maps the terrain that gives birth to diasporan identities, bringing together these rural and urban realities, despite the distinctive nature of our formative years, for Gilroy

“[...]the premise of a thinking “racial” self that is both socialized and unified by its connection with other kindred souls encountered usually, though not always, within the fortified frontiers of those discrete ethnic cultures which also happen to coincide with the contours of a sovereign nation state that guarantees their continuity" (Gilroy 1993, 31).

Out of this description of the liminal threshold that postcolonial subjects are contracted into from birth, we understand that to live in this world is to continually resist the colonial administrative processes which constantly threaten one’s survival. Claudette Johnson, Manchester-born artist and contemporary of Sonia Boyce, Lubaina Himid, Keith Piper, Donald Rodney, and Marlene Smith, wrote of these womanist sensibilities:

“The experience of near annihilation is the ghost that haunts the lives of [Black] women in Britain daily. The price of our survival has been the loss of our sense of ownership of both land and body. The ownership of our ancestors’ bodies was in the hands of slave owners. The horrors of slavery and racism have left us with the knowledge that every aspect of our existence is open to abuse[...] This is reinforced by the experience of a kind of social and cultural invisibility [...] As women, our sexuality has been the focus of grotesque myths and imaginings” (Johnson n.d., 12-4).

Our research around black diasporan feminisms and geographies does not suggest that peoples emerging from the black diaspora don't belong anywhere. Rather, we are the foundation of everywhere. But African Americans have always had a close, particular, and fraught relationship to the land. We have both studied the birth of the modern environmental justice movement, which is located in the struggles and organization of predominantly African American and communities of color in Warren County, North Carolina in 1982. 1 Their ancestors were forced into the labor of being the caretakers of the land, and they have lived on, cultivated, and made the land productive. Running counter to this are narratives of distance from the land, “Slavery, so the argument goes, produced a fundamental distrust of the rural and disdain for nature, a phenomenon that continues to inflect African American culture and expression into the twenty-first century” (Rusert, 2010, 149). Outside of the US, and especially in the UK, one could say that the diaspora shares those same fears, experiences similar structures of racism and exclusion whereby we locate the double consciousness of our historical selves: “...the historic personal and the personal historic” (O’Grady 1994, 6). These are silos of histories fermenting the Jim Crow era and terrorism of lynchings, the KKK into our current carceral states. These histories exemplify the interconnectedness of the shrinking of publicly-owned lands and the racism and hyper-visibility experienced by people of color in the great outdoors, and a distrust rooted in the realities of environmental racism.

We have taken up positions of resistance within the exhibition, The Last Place They Thought Of, in this case, through Harriet Jacobs’ testimony. We recognize in this slave narrative a ‘kindred soul’ and the emergence of a strain of black feminist thought that gave voice to the intersection of race and gender before the abolition of slavery, even. And further than that, her narrative forges a language steeped in space, from the plantations that enslaved her to the garret that enclosed her for seven years and transformed her body, to the liberated northern states that were her refuge—one that argues for the intersection then of space, gender and race. We write as mediators invested in the choreographing of our terrains, historically, contemporaneously, fictionally within structures that welcome and nourish calls for liberation:

“So that the question of how to bring movements together is also a question of the kind of language one uses and the consciousness one tries to impart. I think it’s important to insist on the intersectionality of movements. In the abolition movement, we’ve been trying to find ways to talk about Palestine so that people who are attracted to a campaign to dismantle prisons in the US will also think about the need to end occupation in Palestine. It can’t be an afterthought. It has to be part of the ongoing analysis” (Davis 2016, 21).

We are positioning ourselves as culturally productive worker bees conscious of transnational solidarity movements and ideologies, multiple freedom struggles, and human rights violations.

Riffing off Gilroy’s motif of the slave ship as a “chronotype,”(Gilroy 1993, 4) we understand white supremacist neoliberal capitalist patriarchy is a gargantuan vessel with the wind in its sails, charting and consuming the world at its leisure, vomiting its waste with abandon, free from shame, splattering the rest of us with its bile. This ghost ship is subject to “the rule of nobody”, to borrow Hannah Arendt’s phrase from On Violence, because it is the luxury liner for the kings of bureaucracy. Neoliberal Globalization continues with the overarching goal of profiting from the indiscriminate extraction, and destruction of our earth’s resources, human and non-human. The construction of race—if we dare call it a generative space—has inadvertently fostered solidarities that can assist our efforts to collectively make sense of the realities that we, as individual black women, have experienced, and read about: our ancestors stowed, entrapped, thrown overboard pregnant, whipped, maimed, lynched. These solidarities ask us to land ashore, to escape these perilous seas, to look for ground that isn't smoldering and scorched,2 a ground that no longer contains our kin as “the wretched of the earth.” Can landscapes become spaces for tilling, propagating, and harvesting identities that are inclusive and in a state of renewal and growth? As opposed to the reductive, exclusionary construction of, say “…Englishness [that] was, only by marginalizing, dispossessing, displacing and forgetting other ethnicities. This precisely is the politics of ethnicity predicated on difference and diversity" (Hall 1996, 441).

Montserrat’s work clears space to nurture conversations about race, blackness, anti-racism, and decolonial strategies, in order to contribute towards new pedagogical approaches, and towards writing more complicated histories that center stories of oppression, victimization, genocide, in a historical materialist way. In other words, she works to include the theoretical and philosophical movements unfolding at the same time, the social experiments, and the individual joys and passions of people living through these moments. Of course, depending on one’s position there are variable access points to certain knowledges. Institutional structures do not allow everyone equal access; the mechanics of structural racism and gendered and sexed inequities steer and fuel the gluttonous vessel of our white supremacist neo-liberal capitalist patriarchy.

We are working towards equitable relationships, between ourselves and the earth. These relationships are not yet the dominant framework ensuring the safety and health of our world. We have often thought about Ingrid Pollard’s photo-text series, Pastoral Interlude (1987) in relation to questions around rural belongings, estrangements, and alienations. The work depicts the artist, in a variety of solitary rural scenes that are synonymous with a bucolic English countryside; replete with rolling hills, overcast skies, and hedgerows demarcating land. One hand-tinted silver gelatin photo, shows the artist, seated on a stone wall with a camera resting in her lap, her back inches from a prominent barbed wire fence, staring intently out of the frame away from us with text below that reads:

"Pastoral interlude"

…it's as if the black experience is only ever lived within an urban environment. I thought I liked the Lake District; where I wandered lonely as a black face in a sea of white. A visit to the countryside is always accompanied by a feeling of unease; dread…(Ingrid Pollard. Pastoral Interlude. Photograph, (1987))

Through the lens of landscape; as genre, whether British landscape painting, photography, or literature (Wordsworth) Pollard is envisaging and interrogating who belongs in the English countryside, who has access, and through this work begins to point to some historical processes that are responsible for these notions of belonging. Contemporaneous to this series, Pollard was active with BEN (Black Environmental Network), a since-disbanded Birmingham-based organization she helped to found that “worked to enable full ethnic participation in the built and natural environment.” (BEN, n.d.) BEN did this through a range of activities intended to raise awareness, influence policy, and build a community of ethnically-diverse participants. Both projects—Pastoral Interlude and BEN—take up similar ideas, and they call into focus the reality that the British public imagination holds that black people and people of color belong only within urban spaces. A fallout from imperialist thought, and the further racialised branding of space; cityscapes as crime-addled, full of muggers,3 knife-wielding thugs, gangs, and general scary foreigners; functions to uphold imperialist dichotomies of good and bad, civilised and uncivilised, safe and dangerous, English and ‘other’. Following this, the ideological content (Kinsman 1995, 300) of rural and suburban spaces conjure images of “white faces” engaged in pastoral, wholesome, properly-English, countryside pursuits. Harnessed by our white male media and spectaularised by our white and largely male representatives in government, this ideology acts as a stranglehold on the public imagination, and its potential to think space in relation to our multi-ethnic society. Ingrid Pollard’s work and activism is extremely important to both of us, and Pastoral Interlude is incredibly prescient. For us, this dichotomy of belonging and alienation within a pastoral setting that Pollard draws attention to, becomes a starting point to observe from. We’d cautiously propose this to be a generative place to think about how we form relationships to land, ground, and landscape, through and outside of familial and communal ties. This thinking could possibly lend itself towards renewing or regenerating rural belongings as well as strategies of survival and radical generosity.

The North York moors harbored the unique possibility to furnish one with a particular and distinctive language for nature, survivalist skills rooted in class divisions, and the codes to know how to position a body and voice within the rural landscape. Knowing how the topography has been shaped—through landslides and water-logged midge havens—is part of knowing what is expected of human beings in these geographies and how to survive them. However, Montserrat’s presence, or simply existence, repeatedly needs linguistic, spatial, contextually specific, justification within this natural terrain—both for the largely white population that resides there, as well as for the more ethnically-diverse urban populus. The notion of black lived experiences in English rural locations might often seem too far away from anyone’s experience or expectations that: “...nature itself seems unnatural…” (Rusert, 2010, 151). Gilane Tawadros explains the underlying contradiction that shapes the internal and external turbulences of being black and British: “...the concept of ‘Britishness’ as a single, abiding national identity is seen to contradict the reality of Contemporary Britain as a multicultural society with diverse histories, religions and traditions” (Tawadros, 1988, 41). Montserrat’s childhood involved 4 living off-grid with generated electricity (electricity switched completely off when not in use) and no terrestrial television reception, traversing peat bogs, and daily travel through the longest fjord in Britain, just to reach home. She was shot at by a deerstalker—an event laden with complex specificities of class dynamics, divisions, and privileges nestled in the British countryside; the lays of that land 5—and for her it is very difficult to stress that this lived experience is real. It is a reality that has always been met with an incredulity and disbelief.

These violences, of misrecognition, of being made to feel as other, of being dehumanised, of being subjected to gun shots as land is hunted (and private property is protected), are not so dissimilar to the violences carried out on black bodies within urban spaces. The real threat of violence from landowners’ agency (enshrined in law) to discourage ‘trespassers’ with the use of guns in these supposedly sublime rural settings, constitutes a form of terror and territorialization in the ‘pastoral’ landscape. The British idyll, which is so much a part of the visible narrative in British culture, and a key component of the British national identity (Kinsman 1995, 301), is often experienced by British urban individuals as a sort of gothic fiction; another alienating, excluding, potentially life threatening, vampiric environment. And this makes one fearful of landowners who magnify class distinctions and reinforce the carving up of lands and oppressed subjectivities:

“I am suggesting that when the lands of no one were transformed by plantocracy logics, firming up racial hierarchies of humanness, the question of encounter is often read through our present form of humanness, with spaces for us (inhabited by secular economically comfortable man and positioned in opposition to the underdeveloped impoverished spaces for them) being cast as the locations the oppressed should strive toward” (McKittrick 2013, 9).

3. Rural Belongings

“... black lives are necessarily geographic, but also struggle with discourses that erase and despatialize their sense of place…” (McKittrick 2006, xiii). Thinking through the notion of ‘rural belongings’ and “How bodily geography can be” (44–52) could be one way of countering or challenging this erasure and marginalization or anti-spatialization (unthought-ness, the last place they thought of-ness). But what is a rural belonging? What does it mean to reclaim land, and a relationship to space, and what sort of reclamation or belonging should we be working towards? This is where the “unfolding of thought” can lead towards reparations as a spiritual co-mingling with ecological practices.

5. Jade Montserrat, Untitled (The Wretched of the Earth, After Frantz Fanon), 2018

My dear friend, I know that you, and you alone, possess peace

Freedom will blossom from the skies of prisms**prisons

Magnificent terrifying waterfall flowing like celebration

Dig with elbows where the veridical light touched

Her dyeing garden measured the value of peace

Whose transformation has in fact set the whole process in motion

A contagion of boldness; I made you with love

Perpetual renewal felt as a triumph for life

Spoken with her whole body she consists of the recording that comes from the volcanos

Her body sounds like the silence of that place**pace

Braiding her need in absolute rest within an earthbound altar of joy

Disappearance into appearance; A deep and unremarked possession

The certainty of love and healing, redemption and comfort, the aged twine that binds us

The routine surprise of color; Our names do not appear

Her body, alone, concealed, an act of rebellion

Brought into sharper relief: her body, valued, repaired, something he cannot understand,

has arrived

This amalgam of texts mined from empirical and secondary research belongs to a poetic realm that aims to create future imaginaries. These consider the possibilities of belongings and becomings, and the grazing of words to draw attention to the interconnectedness of beings. The work weaves in, through, and around the potentials of charcoal and its material connection to the earth. The work’s structure attempts at conversation; a responsible “antiphony (call and response)”(Gilroy 1993, 78). Montserrat’s charcoal drawings enlarge texts into site-specific panels that cover the walls of gallery spaces, providing a lens through which to view and reflect on experiences and appropriated textual histories. The first ‘panel,’ as we can call the individual statements that make up the work, prompts a noting of the interdependence of oral and written knowledges. Whilst we read “peace” in “My dear friend, I know that you, and you alone, possess peace,” we might also viscerally acknowledge that we are consuming (whilst being consumed by) a “piece,” an artwork.

Montserrat modeled the scale of the panels to the scale of her body (also a “piece”—“look at that piece of ass”—her body is prone to objectification) and made the drawing while naked.6 Untitled magnified the centrality of the lone body in the making of the work, turning the body into a material connected to the ground, to the ‘landscape,’ and inevitably sculptural.7 Further her “mortal envelope” (Baldwin, 1969) becomes a device to work through the embodied material conditions that a reciprocity between words, bodies, and materiality, race, gender, and space can address. The vulnerability that is apparent through the sheer and opposingly defiant act of nakedness troubles our feminisms. Placed naked in the space of the gallery we might become alert to the words and deeds indicated within the text panels charging the material, charcoal, with the tensions and strength demanded by the female naked laboring body. Drawing on gallery walls with charcoal, material darkness, Montserrat’s body covered in the dirt of the work of it, further calls to mind the north of England's coal mining and cotton mill heritage, and emphasises the labor that generates and is required by a creative practice, by drawing on the links between industrial capitalism and a neo-liberal capitalist art economy. The space becomes catalyst, just as charcoal can be thought of as a binding catalyst. Audiences of the work occupy space through it and take it with them, blackening, creating anew, trailing, creating pathways, smudging together. We stand with Audre Lorde, amidst this ‘mess’, who says “[...]we must never close our eyes to the terror, to the chaos which is Black which is creative which is female which is dark which is rejected which is messy which is...” (Lorde 1984, 101).

The futility of Montserrat’s laboring body, contracted to make an impermanent artwork, attempts to memorialise and activate decolonisation strategies and resistance movements, unearthing psychophysical threats and complicity. The words “Her body, alone, concealed, an act of rebellion” are reminiscent of Harriet Jacobs’ story, a women who escaped slavery, in part by stowing away and effectively imprisoning herself in her grandmother’s attic in “the last place they thought of” (Jacobs [1861] 2001, 98). Jean Fagan Yellin reminds us, in her introduction to “Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl,” that Jacobs “did nothing but read and sew” (vi) in her isolation. For Montserrat, this act of creativity, of giving voice to and exchanging experiences, the “memories within”8, with the fictional and imaginary, suggests not escapism but survival, not internalisation but celebration and joy. It speaks of the urgency of creativity and culture to be renewed, transformed, treasured, shared, and embedded as life-giving. How we equip ourselves to emerge as containers for the screams of slavery, for reading testimonials like Jacobs’s is a coursing scourge. How do we listen when the pains are gagged and internalized? When the words terrify our minds from the vulnerabilities that seep from empathy or forgiveness for perpetrators and profiteers? How does one begin to find language for indescribable abuse: “The degradations, the wrongs, the vices, that grow out of slavery, are more than I can describe” (Jacobs [1861] 2001, 26).

Writing about our black literary history Toni Morrison notes we were “...seldom invited to participate in the discourse even when we were its topic” (Morrison 1995, 91). Morrison in the same essay describes a strategy employed by black writers speaking of their bondage, galvanised in the knowledge that “literacy was power”, whilst up against forms of etiquette and entrenched white fragility and innocence during the Age of Enlightenment (and Scientific Racism) (89), by adopting methods of writing that were palatable to their readers: “it was extremely important, as you can imagine, for the writers of these narratives to appear as objective as possible—not to offend the reader by being too angry, or by showing too much outrage, or by calling the reader names.” (Morrison 1995, 87). A connection could be made between that strategy, and Untitled (The Wretched of the Earth, After Frantz Fanon), a piece that opens dialogues in order to center practices like restorative justice. The etiquettes necessary to succeed in white western societies—the respectability politics or social conservatism that still permeate and impede our dialogue, relationships and social mobility in the UK, are similar to those strategies employed in slave narratives. We are both aware of the problematic nature of this—of becoming complicit in the use of the colonial tools (here, the English language) that not only favors and reproduces constructed binaries, but also dehumanizes, censors, silences and gags: “As determined as these black writers were to persuade the reader of evil slavery, they also complimented him by assuming his nobility of heart and his high-mindedness.[...] They tried to summon up his finer nature in order to encourage him to employ it” (88). Gilroy, again, reinforces this double bind: “It may be grounded in communication, but this form of interaction is not an equivalent and idealized exchange between equal citizens who reciprocate their regard for each other in grammatically unified speech” (Gilroy 1993, 57). Alongside this, we deeply believe that poetics has the potential to function as the trickster: “... think, for example, about words as tools for doing things, and to think of strategy not as the absence or bracketing of thought (as strategy is often thought) but as the unfolding of thought” (Ahmed 2012, 5).

In this work Montserrat ties the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the prison industrial complex, noting the black Atlantic as a site of navigating communications and communicating our navigations in “Freedom will blossom from the skies of prisms**prisons,” graffiti remembered from her train ride from Philadelphia airport to the ICA in April 2018 to install Untitled…. “Her dyeing garden measured the value of peace” creates the starting point with which to broach a proposal Montserrat has been working on for a decade or so, focusing on regrowth and mortality, entitled People's Garden (2015-ongoing). People’s Garden would culminate in a natural dyeing workshop using plants grown in a community garden—every factor of the process drawing attention to the ethical principles of permaculture. The use of words is a central way for Montserrat to fracture meanings, create etymological connections, expand definitions, blur space; as calls to action, as interlocutors, for locating the static; for movement, for drawing attention to the “absented presence” (McKittrick 2014, 235) of the words: dyeing/dying, peace/piece, prisms/prisons, place/pace. “Like all offspring colonizing and imperial histories, I-we-have to relearn how to conjugate worlds [words] with partial connections and not universals and particulars” (Haraway 2016, 13).

By amplifying words we come to ask whose voice it is that gets amplified, and how structures operate to silence. Who is it that gets to speak? Who is being represented? How does that representation function, and to whose benefit? And why are structural inequities served by streamlined representations? How do we access vocabularies that can articulate our experiences, without censorship or prejudice? 9

The “…dislocating dazzle of ‘whiteness’” (Gilroy 1993, 9); its need to remain pristine and innocent, is reckoned with in the work through the use of white text on a black background. The illuminated, contrasting letters seem to move, shake, quiver, and rumble. Theirs is a manic whiteness trapped by molecular shadows: “Everywhere the years bring to all enough of sin and sorrow; but in slavery the very dawn of life is blackened by these shadows” (Jacobs [1861] 2001, 27). The panels drawn for the ICA in Untitled… negotiate with their neighboring panel’s voice, letting each speak in parallel, as a multiplicity enjoined; drawn to appear to cling on to one another. As such the panels could be said to: move together, be threaded together, rhizomatic, entangling, co-existing, interdependent, a chorus line, and, echoing an intention led by Donna Haraway: “cultivating response-ability...an ecology of practices” (Haraway 2016, 34); these texts aim to confront their companion’s as well as their own internalized complicity.

The position of the viewer becomes complicit in these charcoal wall drawings too; they risk being soiled and dirtied by the dust of the charcoal. This material is also a potential irritant, a contagion of boldness; it is not pleading for cooperative interaction, it glories in not asking for permission to accompany you, nay, you made it your companion, it lives in you. The material is biopolitical, it is a reminder of our bodies’ chemical makeup. Being invested in debates around the planet’s changing climate, we both see charcoal as a capacious material to think through our physical relationship to others, the land, geography, literary histories, and visual art.

Charcoal, as an accumulation of organic matter, ties into Haraway’s ideas about compost-ist structures for organizing human and non-human relationships (Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, 2015, pp. 159-165). Sympoesis, making with;“We become-with one each other or not at all,” (Haraway 2016, 4). To decompose. To live and grieve. In an attempt to chart the breadth of Haraway’s kinship to ecological and decolonial movements, as a life-giving ideology we are threading together, in the spirit of “string-figures,” (Haraway 2016, 2) our personal, local and global political companionships are commitments to

“[...]Communities of Compost [who] understood their task to be to cultivate and invent the arts of living with and for damaged worlds in place, not as an abstraction or type, but as and for those living and dying in ruined places.” (143)

One can extract from matter like peat, compost, and charcoal, thus digging deep into our shared histories. But it is also the potential that we can draw from it; the heat of the idea of it is generative and sustaining. Science and speculative fictions/fabulations propel us in to sensational, potentially combustible, movements. As witnesses to layer upon layer of mulchy matter, we have the potential to adsorb our collective memories onto our molecular make-ups; like specks of charcoal on skin. We propose that in answer to an integral visionary question posed as a rallying cry by Mia Mingus in Octavia’s Brood, a collection of science fiction stories from social justice movements, “How do you teach a history of hate in the name of love?” (Mingus 2015, 116), we examine the evidences, treading very carefully, respectfully, cherishing our combined resources, observing the matters, the feedback, the variables for communing and caring. We are endlessly composting remains vital for creating endings towards becomings: “Perhaps it is necessary to begin everything all over again: to change the nature of the country's exports, and not simply their destination, to re-examine the soil and mineral resources, the rivers, and—why not? —the sun's productivity” (Fanon 1963, 99). The renewal and renewing—of energy, shaping materials together, becoming self-sufficient, being careful to understand what will spoil our composting ventures, planting new seeds in, with, and from it. Put simply then, the possibilities for rural becomings, those we are most invested in, spread earthy mycological spores with complete disregard for segregated lands, concepts of terrain or ownership, or erasures of history and memory.

Notes

1 This protest is largely recognised as the beginning of the environmental justice movement. Environment and land based racism and injustices were rampant before this, of course, but did not capture the imagination and attention of the country in the same way. “In 1982, a small, predominantly African-American community was designated to host a hazardous waste landfill. This landfill would accept PCB-contaminated soil that resulted from illegal dumping of toxic waste along roadways. After removing the contaminated soil, the state of North Carolina considered a number of potential sites to host the landfill, but ultimately settled on this small African-American community. In response to the state's decision, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and others staged a massive protest. More than 500 protesters were arrested, including Dr. Benjamin F, Chavis, Jr., from the United Church of Christ, and Delegate Walter Fauntroy, then a member of the United States House of Representatives from the District of Columbia. While the Warren County protest failed to prevent the siting of the disposal facility, it did provide a national start to the environmental justice movement.”

“Environmental Justice History,” Office of Legacy Management, US Department of Energy, last accessed August 17, 2018, https://www.energy.gov/lm/services/environmental-justice/environmental-justice-history

2 “This normal way of life is rooted in racial condemnation; it is spatially evident in the sites of toxicity, environmental decay, pollution, and militarized action that are inhabited by impoverished communities—geographies described as battlegrounds or as burned, horrific, occupied, sieged, unhealthy, incarcerated, extinct, starved, torn, endangered.” McKittrick 2013, 7

3 See Hall, Stuart et al., 1978. Policing the Crisis for more on the conflation of criminality, race, and class in the 1970s and how it heralded a new era of policing in the UK, and the parallels with the US.

4 Montserrat’s mother still lives in the extant family home, the surrounding land of which is in rapid decline owing to no coherent land management objectives, land misuse and degradation.

5 It would seem that this man was given the deer stalking rights by his landowning employer as a gift. Often the case, either working class men or a very young monied men are momentarily favoured, thrown a bit of autonomy, aimlessly, and granted the run of the land to shoot on by the landowner, part management, mostly recreation. Deer, of course, must be managed, their population kept low, otherwise they can get sick: “Management should aim to maintain healthy deer populations in balance with their environment.” https://www.forestry.gov.uk/pdf/fcpn6.pdf/$FILE/fcpn6.pdf Ideally, a person employed by the landowner, a contractor, or the landowner themselves, would manage the deer, keeping numbers low, in tandem with a comprehnsive, tailored managament plan, observant and respectful of nature’s seasonal care needs. In this case, the deer stalking gig was arguably a benevolent gesture, risk assessments neglected in terms of the stalker’s experience and qualifications, knowledge of land management or legal requirements (he shot down hill aiming for Montserrat mistaking her for a deer, where she was walking on a public road, at dusk on a Sunday - each factor presenting illegal practices). In the third instance, a deer stalker may earn their name and privilege as such through buying the right to shoot the deer as a formal let. This person is shooting deer as recreation, and will be upwardly middle class. For more on deer rights and best practice in England: http://www.thedeerinitiative.co.uk/uploads/guides/194.pdf Montserrat insists on an intersectional argument here when thinking about how to report potential dangers and criminality and who to report them to. In terms of race, gender, and class, the assumptions made that socially-mobile racialised white bodies are at the same time tethered to and burdened by the North Yorks rural landscape, perpetuate the erasures and silencing that reinforce constructions of raced and gendered identities. Authority and policing in this area adopt white patriarchal sensibilities, of a Victorian mould wedded to a Protestant work ethic, and Montserrat fears ruptures between her truth and possible interpretations of such traumas as hysteria; adding to existing mental health issues, a consequence of the structural racism that maintains the neoliberal capitalist patriarchal white supremacist paradigm, accounts like this can be co-opted for oppressive means - weaponizing mental health issues against victims, tailoring absolution for abusive activity.

6 The work is borne out of a previous performance titled No Need for Clothing where Montserrat would produce a wall drawing as a performance, naked, in front of an audience.

7 Thanks to Professor Alan Rice for making this suggestion.

8 Toni Morrison in Sites of memory quotes zora Neale Hurston: “Like the dead-seeming cold rocks, i have memories within that came out of the material that went to make me”. Morrison 1995, 92.

9 “Loss of the power of self-narration is central to the traumatic experience since language is not simply an abstract tool of communication; its origins are corporeal and the means by which the body ‘speaks’ its instinctual drives. To shatter the body is also to fragment the power of speech.” Fisher 2008, 193.

Notes on Contributors

Jade Montserrat (b. London, UK) works at the intersection of performance, drawing, and writing, often embarking on interdisciplinary projects. She is the Stuart Hall Foundation PhD fellow at The Institute for Black Atlantic Research at The University of Central Lancashire. Montserrat lives and works in Scarborough, UK.

Daniella Rose King (b. London, UK) is a curator, writer, and producer who lives and works in Philadelphia, PA. King is the 2017-19 Whitney-Lauder Curatorial Fellow at Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania where she recently curated “The Last Place They Thought Of”.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Institutional Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Baldwin, James. 1969. Baldwin’s Nigger. Dir. Horace Ove, infilms.

Davis, Angela Y. 2016. Freedom is A Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine and the foundations of a Movement, edited by F. Barat. Chicago, IL.: Haymarket Books 2016.

Fanon, Frantz. 1963. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

Fisher, Jean. 2008. “Diaspora, Trauma and the Poetics of Remembrance” in Exiles, Diasporas & Strangers, edited by Kobena Mercer, 190-212. Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press.

Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gilroy, Paul. 1987. There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Hutchinson.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. “New Ethnicities,” in Stuart Hall: Critical dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, 442-451. New York: Routledge.

Hall, Stuart et al., 1978. Policing the Crisis. London: Macmillan.

Haraway, Donna. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin,” Environmental Humanities, vol. 6:159-165.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hudson, Peter James. 2014. “The Geographies of Blackness and Anti-Blackness: An Interview with Katherine McKittrick,” The CLR James Journal, 20:1–2 (Fall): 233-240.

Jacobs, Harriet. [1861] 2001. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written By Herself, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin. Mineola, NY.; Dover Publications.

Johnson, Claudette. n.d. “Issues Surrounding the Representation of the Naked Body of a Woman.” Feminist Art News, vol. 3, no. 8, 12-4. Quoted in Eddie Chambers. 2014. Black Artists in British Art History Since the 1950s, I.B. TAURIS: London: 145-6.

Kinsman, Phil. 1995. “Landscape, Race and National Identity: The Photography of Ingrid Pollard” in Area, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec.): 300-310.

Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

McKittrick, Katherine. 2006. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the cartographies of Struggle, ed. Katherine McKittrick. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McKittrick, Katherine. 2013. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17, no. 3: 1–15.

Mingus, Mia. 2015. “Hollow,” in Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, edited by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, 109-121. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Morrison, Toni. 1995. “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, 2d ed., edited by William Zinsser. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin.

O’Grady, Lorraine. 1994. “Some thoughts on diaspora and hybridity: an unpublished slidelecture”, 6. Last accessed August 17, 2018, http://lorraineogrady.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Lorraine-OGrady_Some-thoughts-on-diaspora-and-hybridity-an-unpublished-slide-lecture.pdf.

Rusert, Britt. 2010. “Black Nature: The Question of Race in the Age of Ecology,” Polygraph: An International Journal of Culture & Politics, Issue Topic: Ecology & Ideology 22 (September): 149-66.

Tawadros, Gilane. 1988. “Other Britains, Other Britons,” in Aperture, No. 113, British Photography: Towards a Bigger Picture. (Winter): 40-46.

“About,” Black Environment Network, last accessed August 17, 2018, http://www.ben-network.org.uk/about_ben/intro.asp

“Environmental Justice History,” Office of Legacy Management, US Department of Energy, last accessed August 17, 2018, https://www.energy.gov/lm/services/environmental-justice/environmental-justice-history