On Making Haptic Drawings & Accordion Fold Books | Stephen Vincent

The notion of the haptic is sometimes used in art to refer to a lack of visual depth, so that the eye travels on the surface of an object rather than move into illusionistic depth. I prefer to describe haptic visuality as a kind of seeing that uses the eye like an organ of touch. Pre-Socratic philosophers thought of perception in terms of a contact between the perceived object and the person perceiving. Hence the haptic: looking, we touch the object with our eyes. This image might be a rather painful one, calling up raw, bruised eyeballs scraping against the brute stuff of the world. But I mean it to call up a way of seeing that does not posit a violent distance between the seer and the object, and hence cause pain when the two are brought together. In haptic visuality the contact can be as gentle as a caress […].

—Laura Marks, "Haptic Visuality: Touching with the Eyes," Framework: The Finnish Art Review, 2 (November 2004).

[ …] “fingery eyes” is a phrase attributed to Eva Hayward in her writings on jellyfish. It is the attentiveness, the somatic, the moment by moment movement, that has so much to do with embodied and responsive living right now, with change in some real sense […]

—Carra Stratton, personal correspondence (10 March 2010)

I listen to my now late mother breathing. She’s 93. She is taking an afternoon nap in her bedroom. I am in the "family room" making this haptic. The sounds of her breathing are projected over the speaker on the audio-surveillance system. My pen strokes follow the coarse sound, the circular movement—in and out—and the constant, yet variable rhythm of each breath. In listening so closely, while matching the duration of each breath with a pen stroke, I become aware that I have become at one with her breathing. But it is not just my mother breathing. It suddenly seems as if her breathing—in and out—is the whole world breathing in its most fundamental, primal form and that I and everyone else, no matter where we are, each belong to this breathing motion that precedes time, creates time, and dissolves in time; then, just as inevitably, it creates the next breath, one wave upon another, peaceful, then turbulent, then various, as if our lungs are both at one and a mirror of a global ocean of air that is endlessly turning over and over again. And the rhythm of the breathing is the rhythm, so various and full, at the source and birth of every living thing. And there it is, the haptic unrolling before me out of my pen, rendered mark by mark. And this perhaps mystic thought of my mother, as she ever so slowly begins to pass from the world of her body, that she will pass, as all of us, back into the larger cosmos to an eternal mother that is constantly breathing.

I.

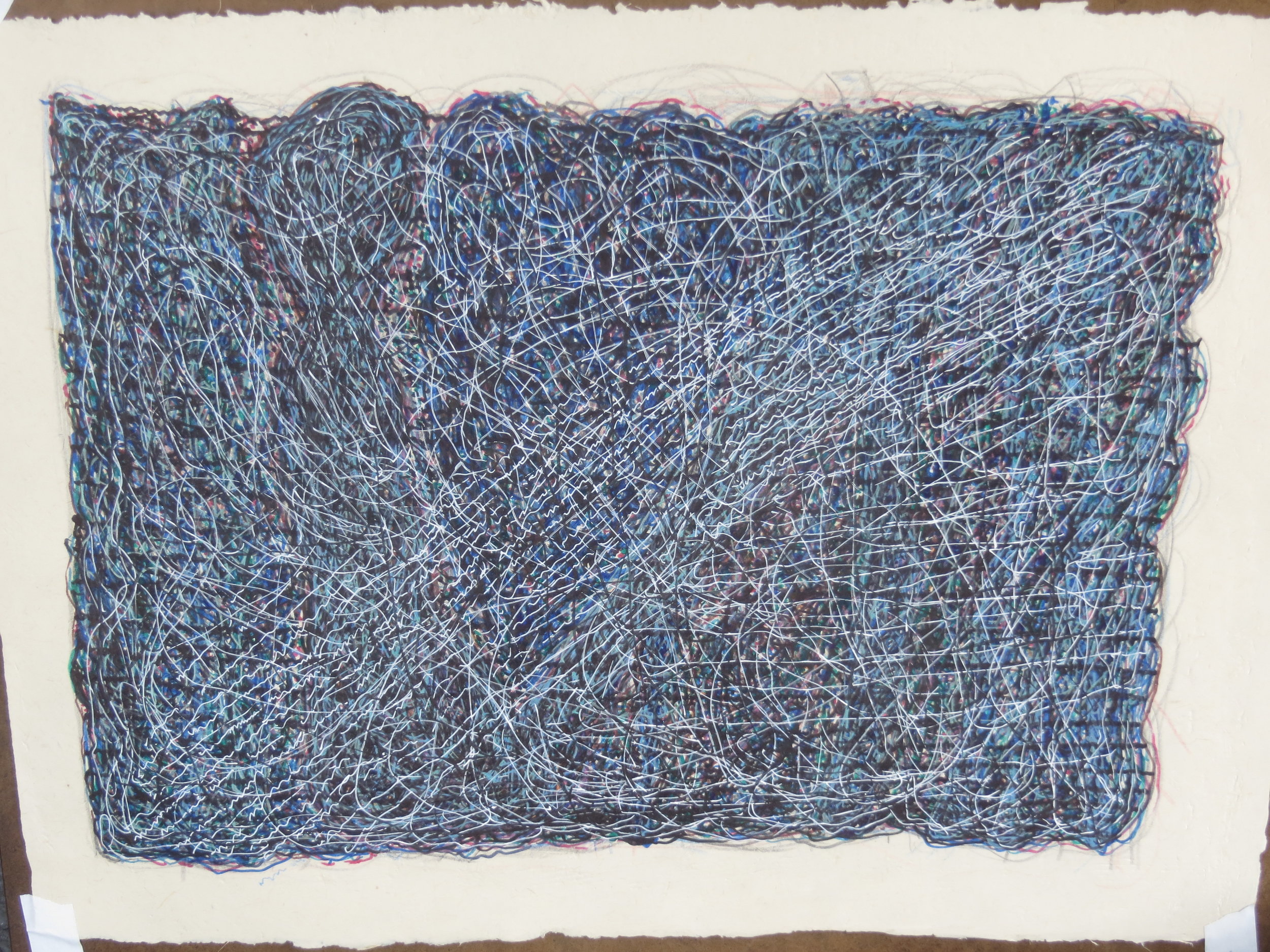

I am a poet, a maker of books, and now considered an artist who makes haptic drawings. Since I most often work with pens I have called my work poetry by other means. Some have asked, what is the connection between making haptics and making poems? When Beverly Dahlen, a longtime friend and poet, pointed out that she could identify a connection between my handwriting and the haptic work, I was unsure at first. Now I think the haptics are one way of writing poetry without words—ultimately, a way of creating a visual score for the work. Even though I make abstract marks, I often sense that my drawing processes are similar to making writing of another, but related sort. It is as if the pens are wands being drawn in, then drawn out during which the marks both experience and explore the pulse of a particular space. Marks that create a simultaneous visual language intent on revealing an alphabet of shapes, one that is both counter-representational, unreadable in any conventional sense, yet surprisingly familiar. Through these marks, this language, one can see and experience its pitches, rhythms and melodies within a simple or complex, particularly laced and woven form. The marks are made in response to the texture of “what is here,” though the definition of “what is here”—the culture of the space—may be much more profound than what initially meets the eye or ear. The process of making these haptic works, by definition, is both visceral and performative. This mark making, this weaving, in the fullest possible use of the senses, constitutes what I call “the sensual apprehension of space.” What we perceive in our "reading" of the drawn work ideally puts us on full alert to what is on “the ground,” these spaces, inner and outer, within which one lives.

Abstract in form, I make my work on archival papers (often handmade Japanese ones made from weeds or other organic matter) of varying dimensions; conversely I draw directly into one of a kind accordion fold books also of diverse dimensions in height, width and number of panels. Drawn primarily with pens with archival inks, the marks (in shades of black, or more recently in color) emerge from a close listening and sensual engagement with the spaces and fields of energy in whatever environment the works are made. Often ‘performed’ as time and/or geographic based projects, I am drawn to working in diverse kinds of situations, such as poetry readings, bars, musical performances, museums. Some projects are defined by city streets, some explore the geography of ocean shores, rural and mountain trails and landscapes. Sometimes I also work in collaboration with musicians.

II. Marginalia: Rene Goldman and Fanny Howe

As a poet and someone who has always loved to go to poetry readings, not surprisingly for the past several years I have made marks in response to poets presenting their own work. I let the pen accompany the sound-shapes and syntax of the spoken word while, at the same time, responding to the intensity, tone, rhythm and particular character of the poet's voice; also included are marks partly in response to any ambient noise from the space and its audience. On a totally unintentional level, shapes may emerge that suggest something about contested figures that the poetry, or in Gladman’s case, her narrative has invoked.

Or in the case of Fanny Howe’s George Oppen Memorial lecture, the lines trace the argument, pauses and issues during her reflections on Simon Weil. Absorbed as I become in the process of making these pieces, I often feel as though I and my pens have joined the performer in a kind of hypnotic dance in which the drawn work becomes one part of a duet; as in improvisational music, the marks vary from being sympathetic, in counter point to (or sometimes being aggressively at odds with) the poet’s voice. In that way the finished drawing may be considered a visual signature, artifact and evidence of what has unfolded and conspired between the poet, the art and audience at a particular location in time. The pieces are usually accomplished on approximately 7 x 10" horizontal sheets. The series now includes approximately 50 or more readings.

III.

Process: To make the work I become as alert as possible to a given space so that my senses and imagination are touched and moved by the particular and multiple sounds, tones, rhythms, movement, and colors that may emerge from within the location. Elements, for example, such as whispered conversations; feet shuffling across a museum floor; sirens and car horns; vibrations from a passing truck; street chatter, the pitch, staccato, and/or melody of a musician’s horn; the collision of ocean waves heading towards shore or the absolute quiet, as recently, of an ancient cave in Capadocia. Whatever the occasion or location, through this process of close listening, my hands, fingers, and pen work to register, respond, and transmit the character, intensity, and duration of the diverse sounds, feel, and more currently, the colors, of a particular site. The drawings invariably become a kind of musical and compositional confluence of these particulars. In this way the medium of the art takes the pulse of an environment to draw as deeply as possible from within whatever may be its depths.

Tools: Depending on what is happening in a particular space I use different kinds of pens: brush point, chisel, and very small to larger gauge metal points (.02, .05., .08, 1. etc.). The brands are usually Micron, Faber Castelli, or Prismatic. The inks are acid free, permanent and archival. The pens—no matter the choice—work to carry the narrowness or the breadth, the color, rhythm and tone of the shape of particular and/or multiple occurring sounds. The pens can go slow, stop or work at great intensity. In one sense, much as in the hands of an improvising musician, they are my instruments at work in collaboration with the larger environment, the space of which I have come to realize is both internal and external, subjective, and objective.

As to the ways the marks appear on paper, the pens do not work according to any prescribed narrative or representational model; there is no beginning, middle and end. In no fixed order, say on a city street, in responding to vibrations and sounds from different sources or directions, I may or may not reposition the pens and work from different places on the page, Initially, for example, one thin, hard point pen may occupy one corner of the paper while listening to the repetitive chirps of small birds; similar to a drummer, the pen will make intense small, repetitive dots until the birds fly off and a large truck, shifting its gears to work its way up the hill, the hand will switch to a brush point pen to make wide, thick strokes; these ones may appear to be calligraphic surges across the paper’s bottom edge.

Initially, the way the pens moved seemed to have a life of their own over which I have only minimal control; the spontaneous seeming moves, perhaps, were similar to the magnetic pulls and stops of the planchette on a Ouija board. (I remember my mother was a demon on that board when I was young!) Yet, I do not want to give the impression that in this process that I work as a totally passive participant merely responding to and letting the spontaneous intelligence of the hands shape the work. On the contrary, what may be called my “subjective side” is also in dialog with the marks that have already shaped the drawing. I am often surprised by the pens being overtaken by what I call an “inner solo.” That is there will be a place inside a drawing where something "takes off" from within; its a subjective kind of inner-listening that propels a release, emergence and configuration of marks that demand to join, respond and re-shape the marks already present in the piece. In fact, as my work has evolved, I have come to the opinion there is no inner or outer space, no pure separation of subjective and objective, but an immersion in which the two are elements that play off, glide, or ‘wing’ together, as well as provoke and resist one another. The skill—and there is skill in doing this well—is to cohere both rhythm and eye with the inner and outer lapping materials; to embrace their various intensities, colors and weights. Indeed the art making is a kind of dance where the partner, or the "other," is always a stranger, and the drawing work is a document of the play, “dance” or “conversation” at hand.

“How do you know where to stop?” is a question I am sometimes asked. In making this work I occasionally find myself in a place unsure of either to stop or continue. The drawing, or section of it, might appear finished, and pleasing or maybe not. The hand—pushed on by an “inner-contrarian” in a spirit of violation—will take over with an insistence that the work continue to unfold, moving to different levels of investigation in ways will totally surprised me. “Trust the hand” early on became my mantra. Yet, in truth, I must say there have been times where this liberty would take the drawing into a murky looking trap in which I have had to make a strategic decision as to how best to get “out of the hole.” To move the pens to another position on the page is often the simplest of solutions! Fundamentally I also work with a rule that there are no mistakes. The haptic process—touch and go—is one of continuous transformation. The pens most often stop when a gesture is complete, an emotion is exhausted, and the page, maybe similar to a quilt, has achieved a credible harmony, disturbance and/or balance. With this equation, the decision to stop may leave a page totally full of marks or only minimally so. To be fully honest, I will confess, there have been times when I have thrown out a piece, deeming it unrecoverable. Things do die in the forest!

As I have made this work over several years now, the process and the forms of content are in constant change. Beyond the attention to empirical surfaces of a site, occasionally the marks breed the appearance of unfamiliar ghost figures, ancient seeming calligraphies, and solid geometric shapes. This change began most dramatically while I was at work in a stone re-enforced cave in Cappadocia, Turkey—which, at one time, was the home of an Armenian family, and prior to that, over the last 5,000 years, the probable relatively raw cave home and/or neighborhood of successive generations of pagans, Hittites, Romans, Islamic and Christian converts. The more I got inside the process of this kind of mark making, I came to realize I was also tracing the residual, if not active presences and spirits of the cave’s prior occupants. This may sound either mystical or bizarre to some. But I think it totally likely that whatever material we encounter, in a cave or contemporary modern space, the pens will uncover what is the still living character and presence in the history of that space. The delight I find in the drawing is the way those spaces become visually alive in ways that are different than what is already contained in a formal narrative history and/or museum of artifacts. The haptic drawing—as a kinetic space—becomes a way to break the rhetoric or stereotypes that have attached rigidly attached themselves to those spaces.

There is, however, another third, essential property and participant in my practice: paper. Indeed, in addition to whatever independent impulses that I and other environmental presences bear on the work, it’s important to point out the haptic drawing process is also a conversation with paper. If the work is a dialog, the choice of paper is a mediating presence, indeed both a force and constraint. The smoothness or the granular resistance of different papers either propel or contain different kinds of marks and textures. What I have learned is that the paper is similar to the larger environment of the work; it also possesses its own implicit resistance and character! Indeed making a haptic work, while listening as closely as possible to the material elements within whatever its space, one inevitably wrestles with and works to balance the interplay of three primary and immediate elements: the paper, the pens and the ink. Given the play and force of these restraints, even if wanted, it is not possible to predetermine any visual outcome. The finished artwork, in fact, acquires and possesses a refreshing and liberating visual liberty of its own

IV. Marginalia: Haptics: The Novel

Within the expansive measure of time and space, the accordion fold book format continues to further the exploration of what maybe I should now call, “The Haptic Project.” In addition to making singular large to small drawings, I have made a series of now over 20 primarily one of a kind accordion fold books. I should mention that a strong part of my background is that of a poetry and art book publisher (Momo’s Press & Bedford Arts, Publishers). As a poet artist, I now draw directly into blank books, some handmade and many imported from Japan. The panels of these volumes can be read one-by-one, or stretched out to stand vertically, in a kind of three dimensional sculpture. The format creates the opportunity to make an object that can be viewed from multiple angles; the counterpoint of the different panels make a kind of continuous visual commentary on one another.

From the start, the books have provided the opportunity for geographic, often time based urban and rural projects to explore the shape, character and nature of cities, rural, national and international landscapes. Cities and the titles of a couple suggest the scope of some:

Stephen Vincent. Haptics: Times Square (2011), Ink, 3.25 x 9.5", 50 panels/3 sites/23 drawings. Slipcase and book bound in silk over board. Courtesy of the Artist. For several days I situated my pens, clipboard and pens either sitting at tables on the sidewalk and, for the most part, at a table on the mezzanine floor of McDonalds. There I could look out on the street, or up to the LED screens advertsing coming summer fashion and previews of new movies. Simultaneously I listened and made my haptics in response to the conversations of restaurant staff and customers and local tradesment.backgounded by a sound system which played endless of songs from Broadway musicals the lyrics of many of which celebrated the aspirations of young and hopeful stars and lovers. The drawing work was to stay on the pulse of everything from the dropped fork to Barbara Streisand’s voice rising to the highest ocatave. This is probably one of my most lyric works.

On the simplest level any one of the accordion folds may appear as a map of a landscape actively in motion, a dance, or an undecipherable scripts; some may only see an aesthetic appearing cardiograph of human and energetic pulses. Whatever the observation, such is the property of the viewer. However, as a writer and observer of the work, whether or not of benefit to the viewer, I have begun to include book panels with texts reflective of the ways in which I have experienced my involvement in making the work. Haptics: The Novel is, without a doubt, my most ambitious accordion fold:

Construed in the months of June, July, August, and September 2011, with clipboard in hand, listening spaces include a cold, fogbound San Francisco; the morning kitchen with Miles Davis, Paris 1948, ballads and blues, then back and forth with Glen Gould and Beethoven. Up to the local bar, Irish working class, with Marvin Gaye, Van Morrison, and The Supremes on the jukebox. Up the City high hill to the corner writing-and-drawing bench. Up 10 thousand feet to the Sierra, Vogelsong peak, with robust snowmelt river, and creek; descending to does, bucks, and fawns at play among gray granite, tree, lake. Then Modoc country with fierce, circuitous lava beds; to Astoria, the wide sun-filled Pacific mouth of the Columbia River; then back down to Ashland and the Bard. Mt. Shasta, so high and white, going home. All the while a country, its collective core splintered, dark and angry, while the hand makes marks—tender, aggressive, tenuous—peeling back the skin from what is white or dark or thick; then, ink line by line, to thread, to weave, to shade into one, or several, fabrics, then breaking those surfaces apart again and again, shredding each until some fundamental mark joins another mark and another, until (through all this darkness) something luminous appears among new textures, shapes, erasures. It is as if an unexpected stranger arrives and, when it is right, astonishes with an absolute, yet familiar, otherness, each new page/chapter a fiction, neo-fiction, a multiple trace, a dissolving dream, a nocturnal cartography within a cartography. Shadows of a forgotten alphabet, a sonic infrastructure spelled out in a forest of fluid marks. A music—mark by mark—now raining specifics: rhythmic, concrete, & continuous.

I find it helplful to realize that haptic marks are not limited to the interventional presence of an art piece. In practice I see the visual presence of these marks as an inherent part of everyday observation. Wherever there is either a large collision and/or even the smallest growth, fissure or natural rubbing together of objects in space, there is a a leave taking of one kind of mark or other. Whether the outline of cracks that appear in a tree trunk while it grows or dies, or similar such in a mountain granite wall, or the scar shape left on a person’s arm, they provide evidence; each informs a history of the space wherein they are found. We might also call those marks the fundamental formation of a calligraphy, an alphabet in which the marks, as ever-changing as they will be, signify the making of both a past and a present. The haptic drawing, in that sense, is the manifestation of a calligraphy that both precedes and ultimately advances the making of print and formal texts. It is the space, for example, in which we live and work before we get to the making and writing of poetry. I will save the construction of that connection to a later day. I will suggest, however, that much of the current intrigue with the haptic space may be attributed to an exhaustion with much contemporary language. There is a growing collective sense, for example, that what has been accomplished within the conventions and language of the poem—let alone what else—is over and done. What is wanted to be articulated in the larger collective, let alone the personal one, is not. The challenge of the maker is to make the marks of language fresh again. With the risk of someone once again sounding like a romantic revolutionary, it is continuously time to go back into language’s sources and wells; to explore and refreshed by the word’s origins in fire, earth, ocean, stream and human community. To rediscover, to make an alphabet anew.

About the Author

A longtime resident of San Francisco, Stephen Vincent is a poet, artist, occasional essayist, maker of artist books and noted publisher. He has exhibited work in one person shows at Quay-Braunstein and Steven Wolf Fine Arts in San Francisco and Jack Hanley in New York. In addition to private collections, his drawings and artist books are in the Berkeley Art Museum and Special Collections, Stanford University. His most recent book is After Language / Letters to Jack Spicer (BlazeVox, Publishers).